Two Approaches to Urban Last Mile Delivery

Two Approaches to Urban Last Mile Delivery

By SMU City Perspectives team

Published 2 February, 2026

“As e-commerce becomes more prevalent, last mile delivery has to be managed well to ensure that resources are not strained and vehicular pollution does not impact human health. Using a centralised or a peer-to-peer delivery approach depends on many factors to succeed”

Fang Xin

Associate Professor of Operations Management, Lee Kong Chian School of Business, Singapore Management University; Program Director, PhD in Business

In brief

- The increase of e-commerce platforms has led to the new challenge of how to organise last-mile deliveries more efficiently.

- The more traditional approach, Urban Consolidation Centres (UCCs), works as a dedicated service hub for multiple e-commerce sellers.

- Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Delivery Platforms act as an online ‘match-making’ marketplace where delivery companies can cooperate.

Amazon, Shoppee, Temu, just some of the bigger names in the ever-growing e-commerce landscape. This e-commerce landscape presents a pressing real-world problem that must be solved in a sustainable and innovative way. The boom in e-commerce and the rapid growth of cities, especially in Asia, have created huge pressure on urban delivery systems.

Logistics groups like DHL have expressed how challenging “last-mile” delivery has become on the ground. According to Statista, in 2024, online marketplaces, like Temu and Amazon, made up the largest share of online purchases worldwide. The question becomes, does this surge in e-commerce, and more importantly, the poor management of last mile delivery, affect a city’s economic, social, and practical environment? In this article, Associate Professor of Operations Management, Fang Xin, discusses his research into e-commerce platforms and urban last-mile delivery.

So what exactly is last-mile delivery? In Assoc Prof Fang’s research, last-mile delivery refers to the final step in the supply chain. It is the journey of a package from a local distribution centre to its end destination,usually the customer’s doorstep. Despite being called “last-mile”, it doesn’t exactly need to be a mile; it essentially means the last leg of the trip that completes the delivery.

“This stage is notorious for being the most costly and challenging part of the fulfilment process. The last mile can account for up to 28% of the total delivery cost for a product,” Assoc Prof Fang says. This is because it often involves navigating through city traffic, making frequent stops, and sometimes delivering one package at a time. All of this is less efficient than moving goods in bulk.

“It’s also especially tricky in urban areas as congested streets increase fuel consumption, slow down delivery times, and generally lower the efficiency of getting things to your door,” he adds.

Last-mile delivery’s effects of this demand on an urban city

When more people live in cities and shop online, the result is a flood of delivery vehicles trying to get goods to customers. This puts intense pressure on a city’s economic, social, and environmental functions, if such logistics are not managed properly.

“Economically, it’s quite inefficient – you get situations like multiple half-empty trucks from different companies all stuck in traffic, which is a waste of fuel and time. The explosion of small, individual e-commerce orders adds complexity and cost, since it’s harder to consolidate those deliveries,” observes Assoc Prof Fang, “Socially and environmentally, the city feels the strain: more delivery vans and motorbikes on the road means more traffic jams and a higher chance of accidents, plus greater noise and air pollution.”

In cities like Beijing, for example, delivery vehicles are a major source of harmful fine particulates with a diameter of 2.5 mm or less (PM2.5) contributing to hazardous air quality. Over time, this pollution can cause respiratory health issues for residents and generally lowers the quality of life.

“That’s why finding smarter ways to handle last-mile delivery is so critical for city well-being. All of this can degrade the quality of urban life – longer commutes, unhealthy air, and overall congestion can make a city much less livable if we don’t manage it properly.” Adds Assoc Prof Fang.

The two approaches to urban last-mile delivery

Assoc Prof Fang’s research focused on how to manage last-mile delivery more effectively. Specifically, it compares two approaches that a city or logistics provider might use to tackle last-mile delivery challenges. One is a more centralised approach, while the other is more of a decentralised one.

Urban Consolidation Centres (UCCs) – This is a more traditional solution. A UCC is essentially a dedicated logistics hub, typically located on the outskirts of the city or just outside the busy centre. Multiple delivery companies (which are called ‘carriers’) drop off their packages at the UCC. The UCC operator (sometimes called a ‘consolidator’) then sorts and bundles these shipments together by destination. Finally, the UCC sends the consolidated shipments into the city using its own fleet of trucks or vans.

The big idea here is that instead of 10 different carriers each sending a half-full truck into downtown, the UCC can send maybe two or three fuller trucks that carry all 10 carriers’ goods. This reduces the total number of vehicles on the road, increases efficiency, and can lower delivery costs due to better economies of scale. In practice, UCCs often require some infrastructure (a warehouse for sorting, for instance) and coordination, and they work best when enough delivery volume goes through them to get those efficiency gains.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Delivery Platforms – A newer, more digital-age solution, inspired by the sharing economy. Instead of physically consolidating packages in one centre, a P2P platform acts as an online marketplace where delivery companies can cooperate.

“Think of it like a matchmaking service for delivery capacity: if one delivery company has extra space in its van, and another company has more packages than it can handle, they can make a deal on the platform. The platform is run by a consolidator as well, but importantly, the platform operator doesn’t own trucks or warehouses – it simply connects carriers who have spare capacity with those who need it.” This approach can increase the utilisation of all those delivery vehicles already out there. Which means more packages per trip on average, because companies help each other out.

The pros and cons

Each model has its strengths. From an efficiency and control standpoint, a UCC can be very powerful since it consolidates many deliveries into a single trunk haul. On the other hand, a P2P platform is very flexible and low-overhead for the operator. The platform doesn’t own trucks or warehouses; it’s more about tech and coordination. The advantage here is financial safety and scalability

The effectiveness of a UCC versus a P2P platform can change based on a couple of key factors. Assoc Prof Fang’s study found that two factors especially matter: the carriers’ own delivery cost and the number of carriers (or volume of deliveries) in the system. According to the research, when the number of carriers (or volume) is sufficiently large, a UCC, which directly takes over deliveries and does so more efficiently, becomes very attractive and can save a lot of money. It not only is more profitable for the operator but also does a better job at reducing congestion and emissions than a platform would.

Conversely, consider a smaller city or a scenario with only a few delivery players: setting up a big UCC operation might not be worthwhile. If there aren’t that many trucks to take off the road in the first place, a UCC could even be underutilised. In such cases, a peer-to-peer platform might perform better. It can flexibly adapt to whoever needs extra help without forcing a large fixed infrastructure into play. The platform can still reduce some inefficiency by matching spare capacity. So, for lower volumes or moderate costs, the platform model can be more practical.

The social-environmental impact

Both the UCC and the P2P platform aim to improve social and environmental outcomes compared to doing nothing – but they do so in different ways, and one can have an edge over the other depending on the scenario.

A well-implemented UCC can significantly reduce the number of vehicles entering a city, which has a direct payoff in lower congestion and emissions. If you imagine 10 carriers each would have sent a truck, but instead two consolidated trucks go in, that would mean eight fewer vehicles clogging the roads. Those UCC trucks are fuller and make efficient delivery routes, so overall you get less fuel burned per package delivered. Socially, that can mean safer streets and a more pleasant urban environment. There is also an opportunity here with UCCs for using greener vehicles – for example, a city could ensure the UCC’s fleet is electric, multiplying the environmental benefits.

The peer-to-peer platform also contributes in a somewhat more subtle way. It doesn’t eliminate vehicles outright, since every carrier still runs trucks, but it makes sure those trucks are used more efficiently. By sharing capacity among carriers, the platform results in fewer total trips or less distance travelled for the same delivery demand, which reduces congestion and pollution to some extent. For example, if one truck can take on deliveries for two companies on the same route, you’ve prevented a duplicate trip. This is a real gain – less traffic than if everyone worked in isolation.

The main barriers against UCCs

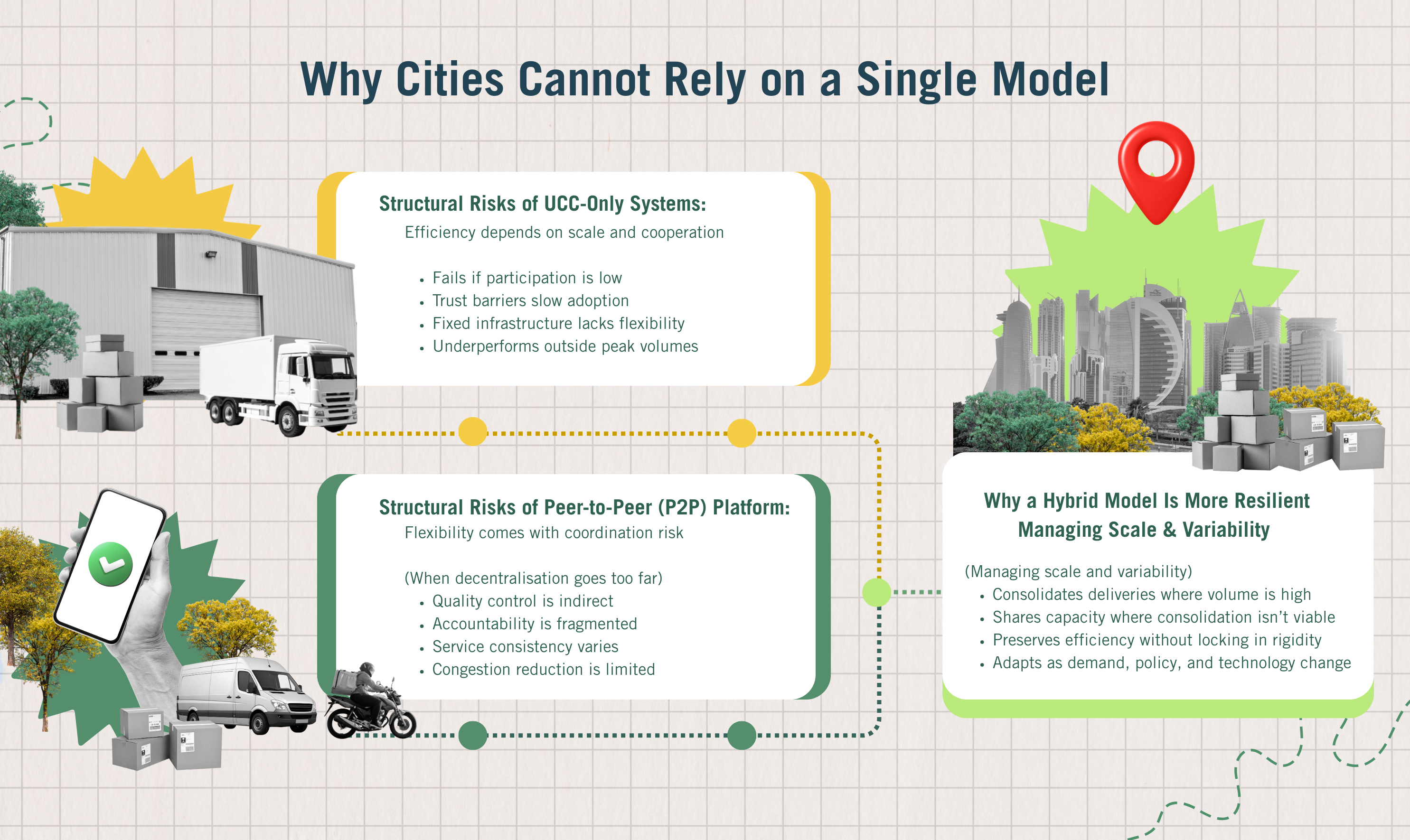

Despite their potential, a lot of UCC initiatives have struggled or even shut down, often because not enough carriers decided to use them.

- The reluctance of carriers to hand over their deliveries to a third-party consolidator. This can happen for a few reasons. Carriers might fear losing direct contact with their customers or losing their competitive edge – they’ve spent years building delivery networks and customer trust, and a UCC could feel like ceding control.

- The economics for the carriers need to make sense. If using the UCC doesn’t save them money (or worse, if it adds cost or hassle), they won’t participate. Many UCCs have to charge a fee for each package delivered, and carriers will compare that to their own cost of delivery. If the difference isn’t big enough, the incentive evaporates.

To overcome these barriers, Assoc Prof Fang believes that UCCs need to build trust and show their value, possibly through a form of industry collaboration. In addition, policymakers can offer incentives such as subsidies, tax breaks, or priority access. For example, a city could subsidise part of the UCC cost in the early stages. The UCC needs to demonstrate robust service quality by delivering parcels on time, with low damage rates, and providing visibility such as tracking information to the carriers. It may be necessary to gradually scale up by starting with a few willing partners, and then publicise the success of the collaboration, to encourage more carriers to join.

The risks of relying on P2P platforms for last-mile delivery in terms of service quality and reliability

He notes that P2P platforms, while innovative, do come with some caveats. Relying on a decentralised network of carriers to fulfil deliveries, maintaining consistent service quality can be challenging. Unlike a UCC, where one operator controls the whole delivery process, a platform is essentially coordinating among many independent players. This means delivery times, customer service standards, and accountability can vary across different carriers on the platform.

“Quality control measures on P2P platforms are typically indirect and hard to monitor,” he says “They might include rating systems, performance scores, or service-level agreements. For instance, the platform can track if Carrier X has a 98% on-time rate and show that information, or even ban carriers that drop too many deliveries.” These help, but they’re not foolproof, he explains, adding that customers might not care which carrier in the network is delivering; they just want their packages on time. So if something goes wrong, the platform operator has to manage customer expectations and complaints, often without having direct control over the people actually doing the delivery.

Another risk is communication and handling of parcels. If a package changes hands between carriers (imagine Carrier A hands it to Carrier B through a platform match), there’s a risk of mishandling or loss if processes aren’t well synchronised.

“While P2P platforms can be very efficient, an over-reliance on them means you have to have strong mechanisms in place to ensure quality and reliability. Platforms may mitigate these risks by carefully vetting participants (only allowing reputable carriers on the platform), using technology to provide real-time tracking and quick re-routing when needed, and maintaining insurance or guarantees for shippers,” says Assoc Prof Fang.

A hybrid approach?

“While our study analysed UCC and P2P as distinct alternatives, there’s nothing stopping a city or a company from combining the two in creative ways. In fact, a hybrid approach might emerge as the most practical in many places.” Says Assoc Prof Fang. “A hybrid just means applying those in different parts of the network simultaneously.”

For example, a city could have a UCC facility at its outskirts to do the heavy lifting of consolidation for the busiest part of the city, but also run a platform that allows independent carriers to exchange capacity for areas or times that the UCC isn’t covering. The UCC element ensures that where volume is very high, you get maximum efficiency by consolidating deliveries by taking advantage of the UCC’s strength of economy of scale. Meanwhile, the platform element could ensure that, beyond the UCC’s scope, carriers are still coordinating rather than working in silos, effectively filling the gaps and peak times with shared capacity.

Another way to hybridise might be a system where smaller UCC “micro-hubs” are distributed in a city, and a platform coordinates between those hubs and carriers – blending physical consolidation with digital matchmaking. “Hybridisation is not only possible, it might be optimal: use consolidation where it yields big returns, and use peer-to-peer sharing where direct consolidation isn’t feasible. Cities might incorporate both strategies, and our research offers a framework to decide the mix: where volume is above the threshold, lean on UCC, where below, lean on P2P. ” Adds Assoc Prof Fang.

The long-term social and environmental impacts

According to Assoc Prof Fang, envisioning the long-term, city-wide environmental and social effects of each model is a bit of, what he calls, a “futures” exercise, but one can make educated projections.

If a city (or many cities) predominantly adopts the UCC model, one might see a future where urban freight transport is highly consolidated. In day-to-day terms, that could mean far fewer delivery vehicles congesting city streets during peak hours, because most of the goods are being funnelled through a handful of well-organised centres. Imagine major cities with UCCs acting like big switching stations for freight – a lot of the chaos we associate with delivery could be reduced.

Environmentally, this scenario is quite positive: – think quieter streets, safer pedestrian environments, and maybe even the reclaiming of some road space for public use because you don’t need as many trucks pounding the pavement.

Now, if a city predominantly adopts the P2P platform model, the long-term picture looks a bit different. Assoc Prof Fang Xin sees it this way, “As e-commerce becomes more prevalent, last mile delivery has to be managed well to ensure that resources are not strained and vehicular pollution does not impact human health. Using a centralised or a peer-to-peer delivery approach depends on many factors to succeed - In reality, I suspect many large cities will use both, or switch strategies as technology and policy evolve. The hope is that, whichever path is taken, the end result supports the sustainable growth of cities, especially those in rapidly growing regions like Asia, so that we can enjoy the convenience of e-commerce and city living without sacrificing air quality, public space, or quality of life. Each model has a role to play in that future, and the research helps indicate where each fits best.”

Methodology & References

DENG, Qiyuan; FANG, Xin; and LIM, Yun Fong. Urban consolidation center or peer-to-peer platform? The solution to urban last-mile delivery. (2021). Production and Operations Management. 30, (4), 997-1013. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lkcsb_research/6695