Living in Diversity: Singapore’s Unique Ethnic Integration Policy

Living in Diversity: Singapore’s Unique Ethnic Integration Policy

By SMU City Perspectives team

Published 2 February, 2026

“We are trying to get people to become ‘colour blind’. There are already so many reasons to fight with each other over about, we’re just trying to remove one of them.”

Edward Ti

Associate Professor of Law, Yong Pung How School of Law, Singapore Management University; Associate Dean (Undergraduate Curriculum and Teaching)

In brief

- Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy is structured to reflect the national average racial makeup.

- Most of Singapore’s population lives in public housing.

- Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy isn’t a copy-paste solution that can be applied in every other context.

Singapore, along with Malaysia, is a former British colony. It’s a very small country, but, much like Malaysia, it is significantly racially diverse. This is especially true when comparing it to other countries in the Southeast Asian region.

According to Statista, as of June 2025, Singapore reported 3.09 million ethnic Chinese residents, 569, 130 Malay residents, 379, 100 Indian residents, and 147, 210 residents that fall under what they call ‘Others’.

In recent years, the world has seen the rise of far-right, anti-immigrant, and anti-diversity sentiments in the Western world. In the east, specifically Southeast Asia, Singapore has put diversity into policy. The policy in question is the Ethnic Integration Policy, a well-known policy in Singapore, yet not often referenced outside of the country. In this article, Edward Ti, Associate Professor of Law, discusses his research into the Ethnic Integration Policy and what other countries could take away from Singapore.

Singapore’s Ethnic Integration Policy: What is it?

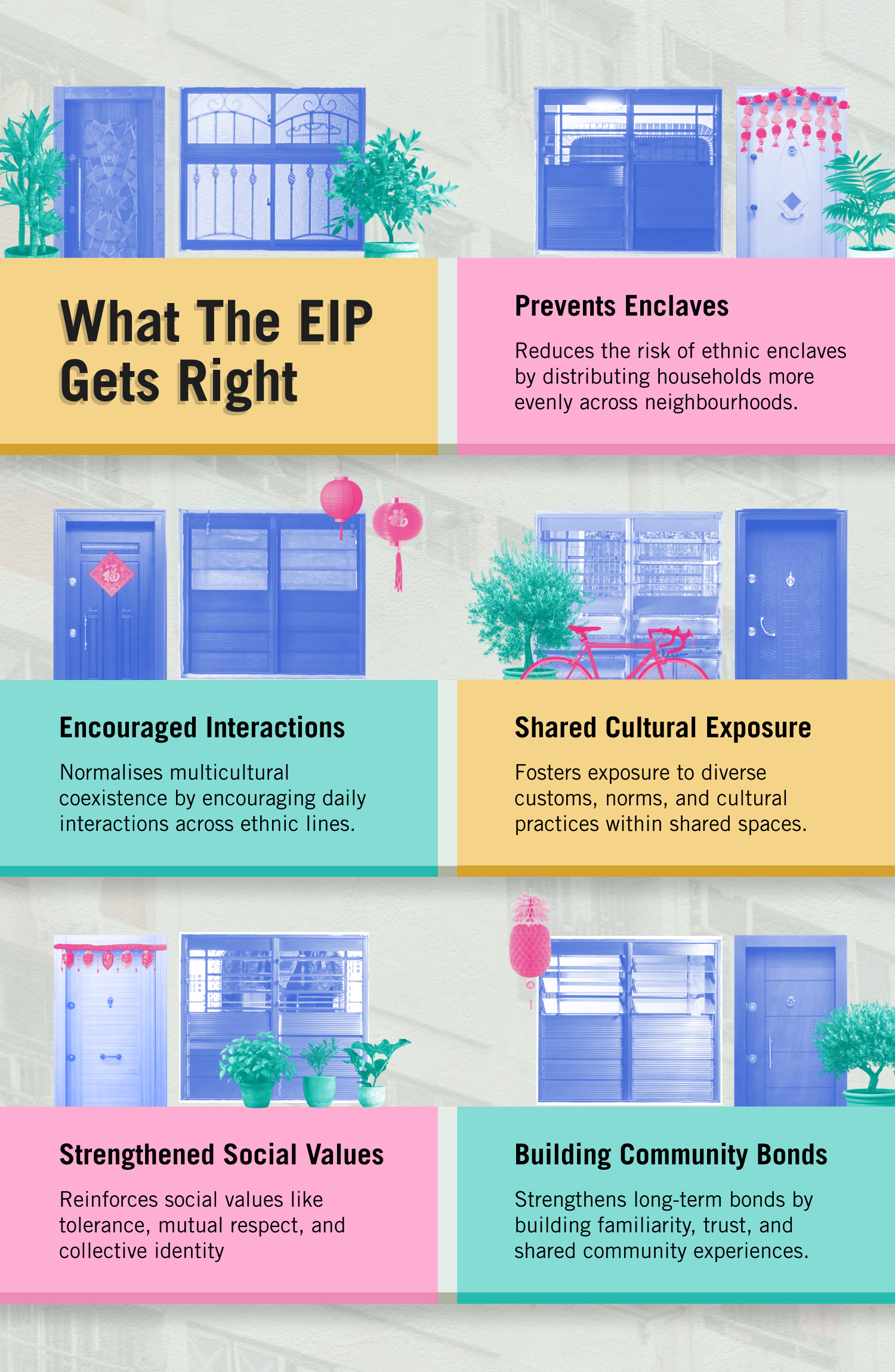

Introduced in 1989, the EIP aims to maintain a diverse mix of ethnicities in public housing estates, prevent the formation of racial enclaves, and encourage racial integration in Singapore. Implemented across all ethnic groups, the EIP sets limits on the percentage of a block or neighbourhood that can be occupied by a specific ethnicity.

The EIP aims to create more opportunities for organic interactions. Essentially, on every block, there will be some representation from the Chinese, Malay, and Indian populations. This conceptually creates a sense of familiarity throughout people’s daily life.

“I think we are the only country in the world to have this kind of integration, and it's part and parcel of public housing”, says Assoc Prof Edward Ti. Singapore public housing is home to around 80% of the population, covering every socio-economic class. This contrasts with how public housing is set up in other countries, where public housing is used by those in lower-income brackets.

In 1989, Singapore’s then-Minister for National Development S. Dhanabalan drew attention to the emergence of ethnic enclaves in Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates during a speech to community leaders. While the Government had successfully dispersed communal enclaves in the 1960s and 1970s through a large-scale resettlement and public housing initiative, Mr Dhanabalan acknowledged that such a comprehensive programme was no longer feasible in the 1980s due to extensive urban development. Because of this, the EIP was introduced as a proactive measure to address the issue of ethnic enclaves and to ensure that public housing reflected the national average of its diverse population. This means that the distribution of housing to each racial category is done by ratio and not by a specific number.

In this regard, the most recent public housing quotas took place in 2010. These quotas specified that the percentages, at the neighbourhood level, were set at 84% for Chinese residents, 22% for Malays, and 12% for Indians and other ethnic minority groups. On the block level, the limits stood at 87% for Chinese occupants, 25% for Malays, and 15% for Indians and other communities. These quotas, of course, do not apply to private housing, this means that if one chooses not to live in public housing, then one would have the freedom to live anywhere.

Indians and other communities. These quotas, of course, do not apply to private housing, this means that if one chooses not to live in public housing, then one would have the freedom to live anywhere.

“If you choose to live in the Housing and Development Board flat, then your ethnicity matters insofar as, within each block and neighbourhood, there is a limit as to how many Chinese or Malays or Indians living within that cluster. The idea behind it is that the government wants to prevent racial enclaves from occurring. There's also a non-citizen quota. So that is to make sure that you also don't have areas which are made up of too many foreigners,” says Assoc Prof Ti.

In 2014, the HDB also implemented the Non-Citizen Quota to prevent the clustering of foreign communities. This policy limits the number of flats that can be entirely rented out to non-Malaysian Non-Citizens in each block and neighbourhood. It is important to note that Malaysian citizens are exempt from this quota.

One important factor about the EIP, is that it is not legislated, but part of a structure of incentives, he says... “This integration at the public housing level is not by law. It is actually by consent, and whoever buys a public flat would be deemed to have consented to this term in the contract and be subject to it,” says Assoc Prof Ti, “For those who must choose public housing the ethnic integration policy comes with it.”

The outcome of the EIP

Currently, 80% of the Singapore population lives in HDB flats, which has testified to the success of the EIP. “The main reason is that we don't have enough land. We have a large population for our land size, and therefore, the only way to accommodate housing demand is to build up. So shortly before independence and after independence, the government engaged in rapid urbanisation and consolidated what you would describe as your kampongs or your villages and essentially built high-rise apartments to meet house people. By implementing the EIP in 1989, it decided to take a more hands-on approach with the public housing market.”

According to The Straits Times, the Ministry of National Development has stated that the EIP has a role in maintaining the multi-cultural fabric of Singapore society: “Without diversity in our HDB estates where the majority of Singaporeans live, opportunities for multicultural interactions will be reduced, and this will ultimately change the tone and complexion of our society.”

Despite the success of the EIP, Assoc Prof Ti is very clear that this policy cannot easily be applied in other countries.

He elaborates: “The real answer is that it’s complicated. Singapore is a unique case; it’s small, and its public housing system can be integrated with this policy. In other countries, public housing is usually reserved for lower-income individuals. While these lower-income groups do tend to have a good portion of ethnic minorities, public housing isn’t split or structured by race.” Assoc Prof Ti’s research in a joint-paper with Assoc Prof Alvin See highlights a key aspect that public housing in Singapore differs from that in the United Kingdom between Singapore's and the UK’s form of public housing. The UK’s public housing is race-neutral - it is needs-based, mainly catering to those who cannot afford private housing.

“In Western countries, it's very difficult to implement this kind of policy, because people will say ‘I should be free to live where I want.’ And because their friends and family members, who are typically of the same ethnicity as them, are living in an area, they will also want to live there. So, over time, a particular area becomes associated with a particular race. You can think of the Bronx area or Chinatown in New York. It is very difficult to legislate something like this because it's about what people regard as basic freedoms, but structures can be there to encourage and incentivise people,” adds Assoc Prof Ti, “It is also a question under the UK constitution, and the European Convention of Human Rights, whether the government is allowed to use race as a differentiating factor, when it should be based on needs.”

Nonetheless, Assoc Prof Ti observes that this doesn’t mean parts of the EIP could not be adapted for use by another country.. The UK has been assigning a certain percentage of housing that must be set aside for lower-income individuals, which indirectly leads to ethnic mixing.

He says: “The UK has been doing something which is very good. What the UK has been doing is that even in the best districts, right, the most expensive districts, a certain percentage of housing must be set aside for the lower income. And because of that you do get indirect ethnic mixing.“

Essentially, the authorities could tell the developer that if they want planning permission to build in a certain place, they must set aside a percentage of the housing for the lower income, and there's a higher chance that the lower income will include non-Caucasians and therefore introduce other ethnicities in that centralised area. This is a way of creating incentives or an environment to encourage interaction with other ethnicities in that centralised area, he added.

He concludes: “I think it's important for us to speak about matters relating to race in a candid and respectful manner. I think that to implement ethnic integration as a policy overseas in another jurisdiction will require incentives. It is less about the use of law . What you want to be saying is ‘ hey, if you do this you get some benefits’ And in the long run, we hope that people will be able to build closer community bonds beyond those we have with our own ethnic groups.”

Methodology & References

- HDB’s Ethnic Integration Policy: Why it still matters. (n.d.). gov.sg. https://www.gov.sg/explainers/hdb-s-ethnic-integration-policy--why-it-still-matters

- TI, Seng Wei, Edward and SEE, Alvin W. L.. Promoting ethnic diversity in public housing: Singapore and England compared. (2023). Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law. Available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sol_research/4317

- Ting, W. P. (2024, August 2). ST Explains: What is the Ethnic Integration Policy and how does it work? The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/st-explains-what-is-the-ethnic-integration-policy-and-how-does-it-work

Written answer by Ministry of National Development on tracking tenure duration and ethnicity of tenants for open-market rental of HDB flats. (2025, September 22). https://www.mnd.gov.sg/newsroom/parliament-matters/q-as/view/written-answer-by-ministry-of-national-development-on-tracking-tenure-duration-and-ethnicity-of-tenants-for-open-market-rental-of-hdb-flats#:~:text=To%20prevent%20the%20formation%20of,action%20against%20the%20flat%20owner