Leaving for love?: How migration to cities is affected by marriage incentives

Leaving for love?: How migration to cities is affected by marriage incentives

By SMU City Perspectives team

Published 25 March, 2024

Why do people choose to live in cities? What is the benefit? Traditionally researchers tend to focus on productivity in the labour market. We would like to introduce a relatively new perspective. We want to think about the benefits in terms of the marriage market.

Jing Li

Associate Professor of Economics, Singapore Management University

In brief

- Young women outnumber young men in cities during periods of economic growth and urbanisation, as shown during the rollout of China’s Special Economic Zones.

- The resulting gender imbalance among young urbanites is more pronounced in larger cities.

- Apart from the labour market, the marriage market offers economists another lens to study how urbanisation creates gender differences in migration incentives.

This article is featured in Special Feature: Raising Cities

During periods of rapid economic growth and urbanisation, young women tend to outnumber young men in cities as the former are more likely to migrate from rural areas to urban areas.

Notably, this gender imbalance is more pronounced in larger cities than in smaller ones. For example, there are 84.48 males for every 100 females in Hong Kong. This gender imbalance brings with it challenges to those who want to marry and start families. So the question is: why is this imbalance happening?

To answer this question, Associate Professor Li Jing from the Singapore Management University and her co-authors studied rural-urban migration in response to the gradual rollout of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) across China, which first began in 1979 with Shenzhen. The research also delves into how gender-specific benefits lead to the higher likelihood of rural women migrating to cities, getting married there and staying away from their hometowns.

Significance of SEZs in China’s economic system

According to the World Bank, SEZs not only offered benefits such as tax breaks to attract investment for growth, but they also catalysed the efficient allocation of resources. By attracting international capital, technology, and technical and managerial expertise, the SEZs stimulated industrial development and China’s greater integration into the global economy. Some 30 million jobs were created and accelerated the development - and urbanisation - of China.

Before the economic reform in 1979, migration within China was rare. Under the hukou system, a household registration system in place since the 1950s, every Chinese citizen was assigned a place of origin recorded on their hukou document. This system divided the population into two categories: rural (individuals who were born and raised in the countryside or smaller towns) and urban (individuals born and raised in cities). The system restricted access to public services and job opportunities based on an individual’s place of origin, which made it difficult for migration.

The first SEZ was established in Shenzhen in 1979 and was followed by SEZs in Zhuhai, Shantou, and Xiamen in 1980. With the establishment of SEZs, there was growing demand for labour in urban areas and many rural residents began to migrate to cities in search of work.

Assoc Prof. Li Jing’s paper noted that in the 1980s, the government began to reform the hukou system. Instead of restricting rural residents from accessing social welfare benefits and public services, the reforms included a temporary residency system that allowed rural residents to obtain temporary urban residency permits. These provided access to certain social welfare benefits and public services in urban areas, although they were not equivalent to an urban hukou.

More reforms to the hukou system came in the 1990s to promote greater social inclusion and mobility. This included the introduction of the “floating population” concept, that recognised the existence of migrant workers and granted them certain legal rights and protections. Recently the hukou system has had even more reforms such as the expansion of social welfare benefits and public services to non-local migrants.

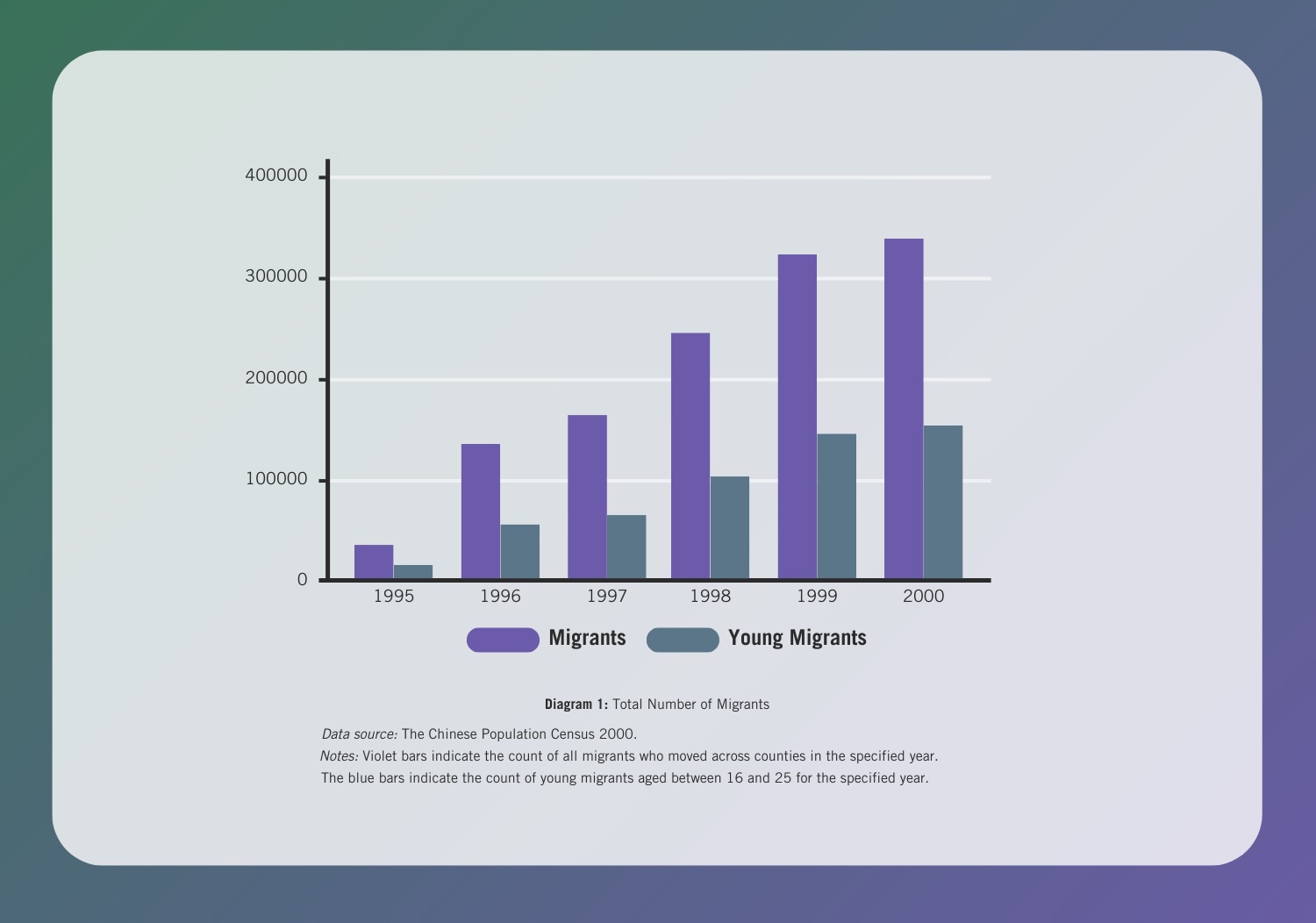

“The establishment of the SEZs was like a policy shock - an instrument explaining the variation of the city size,” says Assoc Prof Li. This economic growth and relaxation of the hukou system brought China an unprecedented wave of internal migration in the 1990s and 2000s.

As more SEZs developed, a large number of migrants from other parts of the country were attracted to the city with its higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions.

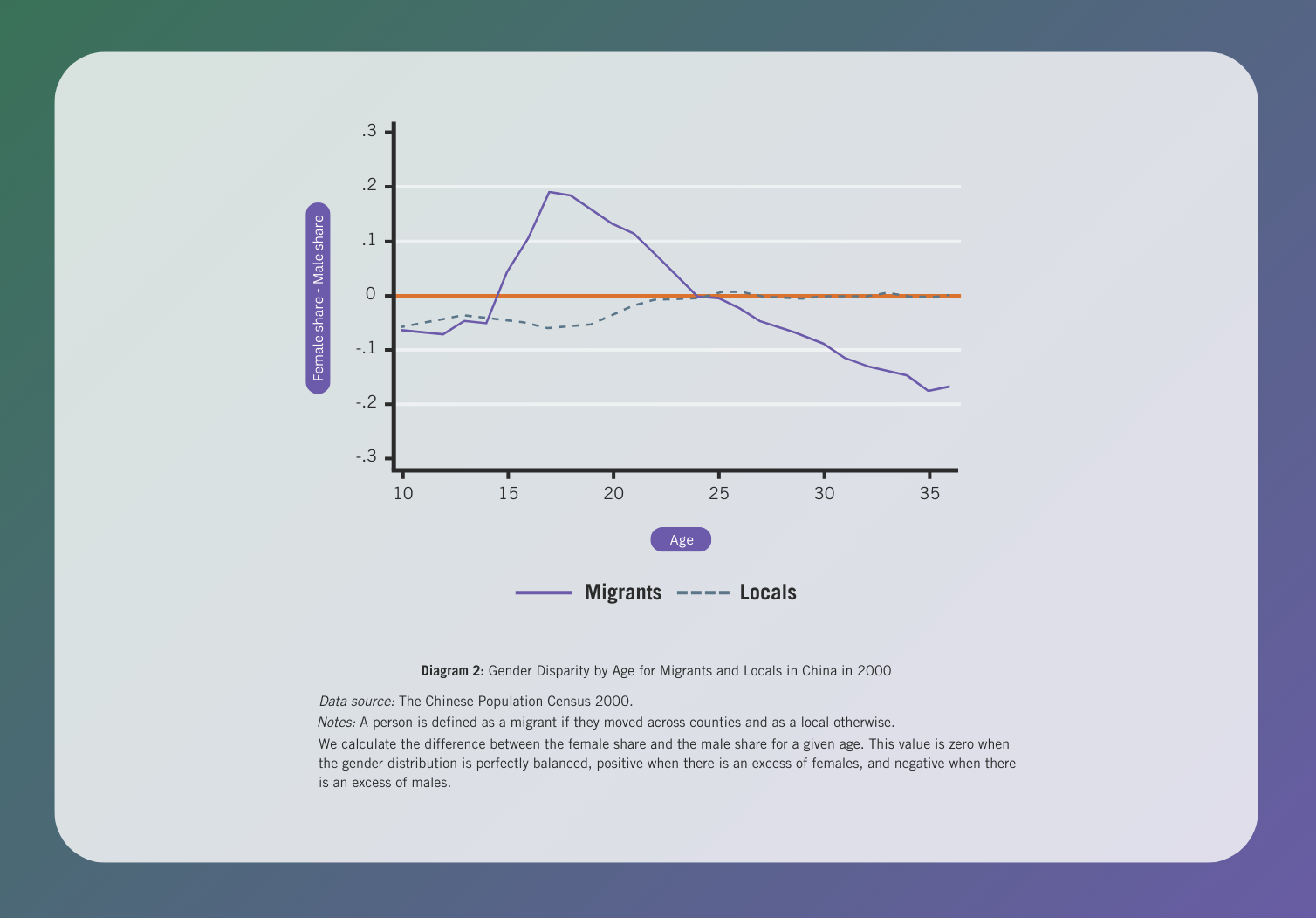

Interestingly, as this graph shows, relative to men, more women are migrating. For women aged between 16 and 25 According to Assoc Prof Li, the gender imbalance among young migrants shows that young women in rural areas were more likely than males to migrate to urban areas. For instance, the figure above shows the excess of female share among locals and migrants by age in 2000: It is positive for migrants between ages 16 and 25, negative for older migrants, and close to zero for locals.

Beyond economic benefits

Cities are important. According to the World Bank, more than half of the global population is living in cities. When more people gather, live, and work in cities, they create a very large labour market pool and there are more opportunities for jobs, education, and personal growth.

Traditionally, economists have tended to focus on the labour market to understand economic gains in cities. Here, Associate Professor Li says she has chosen to focus on the marriage market to analyse how men and women are matched to each other through marriage in cities and how this process also influences other life choices, such as human capital investment and the use of marriage surplus. In particular, she wanted to explore gender imbalances caused by migration to cities and urbanisation.

She explains: “Economists see everything as a market. In a labour market, there are employers and employees. When they find a match, they then come to an agreement that is mutually beneficial for them. In a marriage market, it’s much the same, people enter a marriage agreement when there are gains to both parties. You enhance marriage market matching and create larger gains when you allow people to access a very big marriage market pool.”

Through her research, she found that the gender difference in marital incentives plays a crucial role in this gender imbalance in cities. While education opportunities, available amenities, and differences in industrial composition were possible factors, they did not fully explain the gender difference in migration tendencies.

The marriage market: the main factor for gender imbalance in growing cities

According to Assoc Prof Li’s research, one of the main reasons for gender imbalance in cities is that young women are more likely driven by marriage market incentives. Her research found that the opening of an SEZ in a county increases the inflow of young female migrants by 43.28% and that of young male migrants by 35.17%.

The asymmetry arises from the tradition of hypergamy – a term referring to the practice of women tending to marry men of a higher socioeconomic status than their own – which has existed across the world for centuries. The interplay between labour and marriage markets increases the benefits of urban living and makes it more appealing for young women. Hence, when a city becomes larger due to an economic boom, Assoc Prof Li observed that women had a higher incentive to migrate.

In other words, the prospect of marrying someone of a higher socio-economic status also increases in large urban areas.

Another important practice contributing to this asymmetry for women, according to Assoc Prof Li, is patrilocal practices. This is where, after marriage, women move into their husbands’ houses and/or with their husbands’ families. This practice is especially evident in China, South Korea, Japan, some South East Asian countries like Singapore and even observable in some Western nations. While this practice can have some negative implications, Assoc Prof Li says that it forms additional incentive for young women to migrate to urban areas. “ So this means that we now have an additional benefit coming from marrying a man in a city. If a woman marries a man living in the city, there is a higher chance for her to live there.”

“There is a very important benefit big cities provide to the marriage market. When the city grows bigger so does the marriage market. That's going to benefit the young people, in particular, young women,” says Assoc Prof Li.

Effects of gender-differentiated marriage market

A bigger marriage market means more opportunities for those who are looking to get married and start families. This gender imbalance, however, can negatively affect those opportunities, notes Assoc Prof Li.

The widening income and gender divides in the marriage market may have far-reaching implications for social and family stability.

“Let's think about the big cities. You have more women in big cities. The women would have the incentive to actively seek a marriage partner, but there are only this number of men available. Now that leaves them with the incentive to, for example, approach married men. This is why this gender imbalance could be regarded as a threat to the stability of marriages”.

“Conversely, if there are more men than women in rural areas, men still need to find a woman to form a family. If this is not possible, there could be, potentially, a threat of sex-related crime, for example,” she says.

Alongside the issues caused by gender imbalances, spatial inequality and the unequal distribution of resources such as healthcare, welfare and public services through different areas are other issues.

“China has tried to introduce a lot of policies that aim to strike a balance for economic growth rate across different regions. Because the country wants to achieve spatial equality in terms of economic development, but it needs to remember that spatial inequality is not just about productivity, it's not just about wages, it’s about the welfare of the people, and the utility of the people rests significantly on their marriage market outcomes,” Assoc Prof Li remarks.

Whether people can get married and have family stability is just as important as their ability to put food on the table. This research has shown that you may achieve material gain through urbanisation, but maybe you are generating a gain at the expense of marriage stability and gender equality, which counteracts that economic gain. In essence, as our global cities continue to grow and evolve, we need to develop a balanced and sustainable society to safeguard people's welfare.

Methodology & References

- China’s Special Economic Zones. Worldbank. (2015). https://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/Event/Africa/Investing%20in%20Africa%20Forum/2015/investing-in-africa-forum-china-and-africa.pdf

- Countries with More Women Than Men 2024. Countries with more women than men 2024. (2024). https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/countries-with-more-women-than-me

- Foster, A. (2016, December 13). Marriage markets. SpringerLink. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2637-1#:~:text=The%20term%20%27marriage%20market%27%20refers,the%20allocation%20of%20marital%20surplus

- Li , J., Koh, Y., Wu, Y., Yi, J., & Zhang, H. (2023, July). Young women in cities . Ink.library.smu.edu.sg. https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3685&context=soe_research

- Overview - Urban Development. World Bank. (2023, April 3). https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/urbandevelopment/overview#:~:text=Today%2C%20some%2056%25%20of%20the,billion%20inhabitants%20%E2%80%93%20live%20in%20cities

- Sen, S. (2019, May 10). Patrilocality is the root of gender discrimination. Rights of Equality - Promoting Gender Equality and Women Empowerment. https://www.rightsofequality.com/patrilocality-roots-of-gender-discrimination/